Interview from Art Writing SVA

Degree Critical, Spring 2018

Interview: Gogy Esparza and Sahar Khraibani

Gogy Esparza. Beirut Youth (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

by Sahar Khraibani

I first met NYC-based, Ecuadorian-American artist Gogy Esparza through mutual friends, and the first time we hung out we ended up walking down Madison Avenue on a Thursday afternoon. On that walk, Gogy told me that he gets his inspiration from the shop windows on this street. This surprised me, because I never took him for an Upper East Side aficionado. My vision of Gogy was that of a warm-hearted individual, who spent the last ten years or so hustling in the gritty art scene, as far away as can be from Madison Avenue. I was living in Beirut in 2016 when he was there shooting for his Beirut Youth project (2017), and though we did not cross paths, the word of his visit spread like wildfire in such a small city. The project, initially tackled the globalization of subcultures, but ultimately showcased the juxtaposition of a diverse culture, where different religions, classes and opinions breed both its chaos and its charm. It later gained a sponsorship from Adidas Originals for the exhibition to tour worldwide. Gogy and I squeezed this conversation between two haircutting appointments at his Chinatown studio. I arrived right after he had finished giving his first haircut of the day. As he sat comfortably in his barber’s chair, we discussed his path as a barber and artist working across film, photography, and fashion.

The following text has been edited for clarity.

Sahar Khraibani: You just came back from showing Beirut Youths in Tokyo. Did that trip change your perspective of the project? How was it perceived there?

Gogy Esparza: Really well. I mean, I don’t want to generalize, but the creative culture in Japan is very curious and anything they find exotic they want to know about. They tend to explore outside cultures and they go all the way: they do all their homework, they ask a lot of questions, and I think they’re very respectful and genuinely curious. That’s why I love it there. And it was great to see their reactions cause they were like “wow, the conditions in the [refugee] camps are really crazy, the history is so complex.” They were willing to ask the right questions, and eager to educate themselves.

SK: I was watching the Beirut Youths videos again, and I was thinking about their content. You know, it’s home for me, and I was thinking of the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp especially because I’ve been there so many times for different reasons. So I have a different relationship to the camp in a way, but I normally don’t like it when people other-ize and exoticize it. Your video didn’t do that. You know, it’s a very specific culture they have in the camp: it’s their own little world, kind of like Chinatown on a smaller and more condensed scale. So I was curious, as someone who had never been to Beirut before, what was your perception of Beirut before going and after going, especially visiting the camps and then areas like Raouche, which is really a mishmash of people from all classes.

SK: But you didn’t.

GE: But I was really naturally attracted to that. I was there when Trump was about to be elected and then there were a couple of documentaries that came out that talked about U.S. relationships with the Middle East. One of our big goals was visiting Mlita in the South and the Hizbollah Museum. There you see the other side, because in the U.S. you only get the U.S.-Israeli side. So a lot of my focus was initially on the history of war. As you know, I’m an immigrant from Ecuador who came to the U.S. with my family. We grew up in the inner city, in the hood, so naturally I kind of gravitate towards these stories of conflict and displacement because I relate to that.

Gogy Esparza. Beirut Youth (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

SK: So you’ve been through a form of displacement?

GE: Exactly. And also assimilation, right? Palestinians here are refugees but in Lebanon they somewhat have no identity. And in Lebanon I think they remind you of that.

SK: Definitely. As a Palestinian, you don’t have a passport or a citizenship. You only have a refugee card, and you’re not allowed to work in certain places or even buy a house. You’re constantly reminded that you don’t belong. I mean unless you’re very rich, there are a lot of class rules that play into this game as well. What was interesting to me was that you went to Beirut at a very specific time: the garbage crisis was at its peak, and the summer was rough, politically and culturally.

GE: I guess initially that was my concept. Beirut is a very progressive place in the Middle East, so there was going to be more free spirited energy there than obviously in Saudi or even Dubai, but what I found there was very different. Inevitably I started realizing that I couldn’t tell people that I was from New York. I couldn’t tell them I was American. I preferred telling them that I’m Ecuadorian because there was a big wall put up, rightfully so, toward the United States. But once you get through that wall with people in Lebanon, it felt just like Latin culture to me: very warm, very giving, inviting. The hosting culture is really beautiful. And also, the Mediterranean Sea. I think the sea had the biggest impact on me. It felt cleansing, calming, almost omnipresent.

Gogy Esparza. Beirut Youth (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

SK: The sea has always been the biggest mystery and inspiration for Beirut. Ultimately, being here in New York and now so far from it, I’m starting to realize why it has such a hold on people. I mean it’s the only place where you can breathe: an open space in a city with no public spaces. It’s the only escape, really. And then people lost their lives in the Mediterranean while trying to migrate and we carry that shame around.

GE: I didn’t think about that…

SK: I mean you see it everyday. What I appreciated in your videos, especially the one about the private beach club Sporting (Raouché, 2017), was that you showed the public beach right next to it. I think you hit on a specific synthesis of Beirut, a non-cliché way of showing what the city is and what it means to live there.

GE: I just tried to be honest because of course I got love at the cliffs of Raouché, but I wasn’t fully down with everybody there. They knew I was an outsider. Like “hey, I went to Sporting too, I was at that private beach,” and I think I showed that. I wasn’t trying to lie. I was eating fish at Sporting and also looking across the bay. I think I was trying to be very objective and factual and just to tell the truth. I wasn’t lying about the conditions in the camp, I wasn’t lying about Raouché. And for me, I always go in both worlds. Even in New York, I like to see every scope of every place. You can come from two different worlds and exist in both at once. Some people can only exist in one world and that’s very sad, but it’s real.

SK: I really appreciated the honesty. I’m very wary of someone coming in from the outside and wanting to apply their own vision to what the place is.

GE: Being a Catholic Latino for me changed how I saw things. We hide behind this veil of conservatism and prayer. People have this fascination with the virgin or the whore, It’s very prevalent throughout the Bible and the years of culture that have come from it, but at the end of the day this strict idea of “right and wrong” creates so much infidelity and so much distrust. You know, I talk about that in my work. I show you the ugly side. I show you the truth, and then I also show you this idealistic vision. I don’t lie. My personal work is very crude and very raw, and you know, it’s not for everybody. I think if you pay attention to the nuances of what I’m trying to say, you understand that I’m very honest about it, and anywhere I’m going to go, I’m going to do that ‘cause that’s who I am. We need to have a dialogue about the truth and our perceived notion of what we feel should be true.

SK: Do you feel like you have a duality in your perception of things? In your art?

GE: Definitely. Being in Japan was amazing and beautiful. It’s like: okay, it’s very clean and pristine and everything is incredibly orderly. All the trains are on time, but at night—or if you go to Shinjuku, the party district—essentially they sell sex dreams there. You as a foreigner cannot go into these places. You cannot document these places, because the Japanese government wants the outside world to only see the pristine side of Japan, to perceive it in a specific light. But Shinjuku is the underbelly of the city, completely run by Yakuza (members of transnational organized crime syndicates originating in Japan). This is the contrast I like to show. In Lebanon, it’s more out there, but the tradition of Arab culture is still very conservative.

SK: Depends where you are geographically in Lebanon.

GE: For sure. And I can’t assume this American standard is the same everywhere else. I can’t. It’s arrogant.

SK: But you also come from a dual identity, I mean you’re from Ecuador, then you moved to Massachusetts, and then to New York. You saw different sides of the world and had an interesting trajectory, and that’s why I think you even see New York in a different way. I mean the first time we hung out, we walked down Madison Avenue, which is an uncomfortable place for me cause I always felt it was for the rich. But you didn’t feel that way.

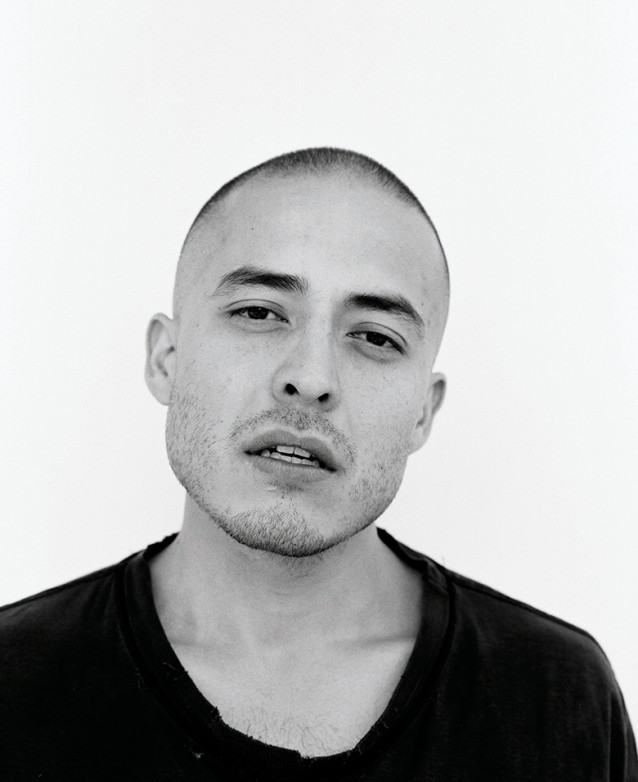

Gogy Esparza. Photo: Ari Marcopoulos.

GE: The thing is, my father was a doctor in Ecuador, and he fought and earned his education coming from nothing. And then he came to the States and his title wasn’t recognized, the only work he could find was in a factory assembly line. He was reduced to that kind of labor. But this guy was a doctor in his culture. Every immigrant has this story. To withstand and remain yourself and assimilate only to a certain degree is respectable and admirable. In Ecuador, he’s able to walk in the poor neighborhoods that he’s from, but he’s an educated person that willfully fought for an education, and he should be entitled to the same levels of consideration as every other person. In New York, or anywhere I go, I feel the same way. I always go to the hood wherever I am travelling, but then I will go to the more expensive neighborhoods and have a drink. I will go to the Louvre and appreciate art. I will challenge myself like that, and I will challenge the environment that is in place. I’m willing to take that risk. I have to dress like them. I’m fair skinned, but I have a shaved head. I have tattoos. I have my mannerisms and a character that let them know I’m not bourgeois. and if you’re unable to accept me, then I will challenge you. Because these people, they tend to stay in their world. They don’t come to my world, or if they do they consume it, from hip-hop to street art.

SK: Or sensationalize it in a way?

GE: Absolutely.

SK: They want to put you in that category and don’t expect of you more levels of culture or integration.

GE: For me, it’s like cutting hair. I know how to give you a fade or a tape up, a line up, a shape up; these are like cuts you get in the hood. But I know how to cut all different types of hair, and also you need different types of techniques to do that and there is a cadence, a layering process. There’s an understanding of how things fall into place in the act of cutting hair. I know how to give a good haircut because I’ve been giving them for so long, but I’ve challenged myself to learn what I don’t know. I should be entitled to appreciate the complexities of any type of world that I choose. You have these creatives challenging themselves by the exposition to a whole new culture, and assimilating the traditions of the pre-existing culture. That’s what New York is, that’s what the infrastructure is. The city was built on a grid system from the very beginning, and it was meant for ease and flow of commerce and culture. That’s embedded in the design of the city, so who am I not to take advantage of that, you know what I mean? In Lebanon, it was important for me to go to Mlita, to go to Dahieh, to Shatila and then yes I was at the trendy Decks On The Beach, and yes I was eating at Restaurant Casablanca, because I wanted to see it all.

SK: It’s part of the culture somehow.

GE: To be honest with you, I understand classism because it exists in Ecuador as well. It’s very classist, and it’s based on the color of your skin. But I don’t agree with that, and I don’t partake in it at all. I’m very vocal about that, and I show that in my work. I chill with all different types of people because I truly believe in that spirit. I believe in the human race. I want this universal prevailing message of struggle and of acceptance.

Beirut Youth will be on view in Los Angeles at HVW8 Gallery on February 22, 2018. It will be the fourth installment of the exhibition. The exhibition was shown in New York City, Dubai, and Tokyo thus far, and planning to close out the tour with an exhibition in Beirut this coming Summer.